Renovation 2

Stoneware basin

Renovating in Italy

It’s now ten years that we have been in Pitigliano, renovating, holidaying and living. We chose Pitigliano, in the hills of La Maremma, southern Tuscany, for several reasons – the town itself; the hot springs of Saturnia; the wonderful beaches south of Argentario, and the countryside all around. Here are a few photos.

We took up the floors and found old tiles which was a wonderful find, but which now need work again because the ceiling of the magazzino (store room) below is deteriorating affecting the floor above. In truth this work was always going to be done, it was just a matter of when – when arrived in 2012.

I made my own stoneware tiles for the kitchen, following the idea of uncovered – ‘found old marble’.

We found the original painted wall and built it around designs incorporating terracotta wall lamps I made. Not everyone would do this or even like it for his or herself, but for us the architectural point of an old house like this, going back in parts to the 17th century – as it it is for local builders – is that you create and reconfigure old aspects and ‘finds’ into the overall look.

The fireplace was completely excavated, set back and made much larger, and we designed a heavy cast iron grill and had it made at a local foundry, so any fire on it would suck up the air and roar up the chimney.

A wood heater (la stufa), for keeping the house warm when a roaring wood fire would create too much heat.

The roof was redone.

Ceilings and a skylight done.

Shutters (le persiane) put up.

Slowly, modestly we are getting the house in shape.

Narratorial Unreliability

Christian Mihai discusses his ideas on unreliable narrators, something he likes to see writers use, and a technique he says he uses himself. Still, he misses a fundamental point – all narrators, storytellers, dramatists, poets, are unreliable. From Homer, Shakespeare to Sartre, no writer tells, gets close to ‘the truth’, even if he or she is prepared to die in the process of collecting all the observable details of a factually based fiction.

Do we trust Tolstoy’s account of Napoleon in War and Peace? Perhaps… if we are Russian.

Narrator unreliability doesn’t have to be a first person account, though the most obvious modernist exploitations of narrator unreliability in fiction use that form. The best approach – for this writer at least – is when the writer sets out to deceive us, and by convincing us that he or she has told the truth, transfers any doubt on narratorial reliability to a reader’s interpretation of the tale.

Pitigliano & La Maremma

Out of the Kiln – Blue and white ceramics

Cannes@fadeout 2012

Journal de France@CANNES

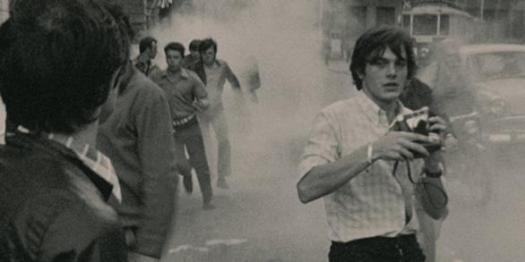

Raymond Depardon and Claudeine Nougaret’s Journal de France, a quiet, inquiet, incisive and drifting study of their fifty-year collaboration and life in photo and cine-journalism.

Journal went straight through the eye to the heart, reminding me of all the driving I have done throughout France on the way to Italy, the footage I have filmed around the globe. The best art reminds of ourselves and our own lives always.

Some of the most arresting cine-images and moments were not North Africa, Venezuela or Czechoslovakia in political turmoil but the still images taken in quite places along French roads.

NormanLloyd@CANNES

Norman Lloyd’s talk in the Salle Buñuel was a lesson in theatre, film technique, Shakespeare, Renoir, Brecht, Chaplin, Welles, Hitchcock and Kazan, and how to keep your mind a steel trap well into your nineties. I don’t know if he eats nothing but blueberries but he must be doing something right.

In an age when aging (see Haneke’s Amour) is often told in tales of sad decline, this man stands out as an object lesson of hope for all. The session was one of the highlights of Cannes in 2012. Holding his audience spellbound, Lloyd, a 97 year-old veteran of acting, directing and production, took listeners through the best part of the pantheon of cinema (the first 60 years of it). What and who he didn’t know simply wasn’t worth pursuing.

Lloyd, stage and film actor

It wasn’t just that he knew so many of those who were crucial to the development of 20th century cinema, it was he knew what they knew and why they knew it – and above all he could tell us how and why he knew what they knew. He understood their brilliance with exacting modesty, placing himself in the role of pupil to all of them. Yet for all intents and purposes he was their equal in collaboration, a creative confidant in so many ways; he travelled through film history with them not because of them. Lloyd’s contribution to film is real, tangible and deep. When he recounted how Hitchcock – a decidedly unpolitical man – with three words to NBC, “I want him” dissolved the McCarthy blacklist era, the entire audience in the Salle was stilled. Lloyd’s part in McCarthy’s ruination was just one anecdote in many. Politically involved and motivated throughout his career, Lloyd was a close friend to Jean Renoir, Chaplin, Welles and Hitchcock. Lloyd was at the heart of theatre and cinema for nearly fifty years. One of the best moments of the night was his recollection of the lines of Bertolt Brecht: “Since the people are displeased by the government, the people must be replaced.” The sharpness of wit, his breadth of cinematic knowledge was stunning.