So from September 1979 I made films for our new once a week magazine TV, hour long program, Here and Now. The same routine for me, a film every week, which morphed into longer films later. Some pieces I did were good stuff even if I say so myself. Yet, the founder of the program, deputy director Stuart W., lamented the lack of journalistic impact. The program without the set-up of Panorama or Newsnight wasn’t news.

After two years a story arrived that gave us our chance—a 1981 official report of by Justice Yang of his special Inquiry into the death of a police inspector, John MacLennan.

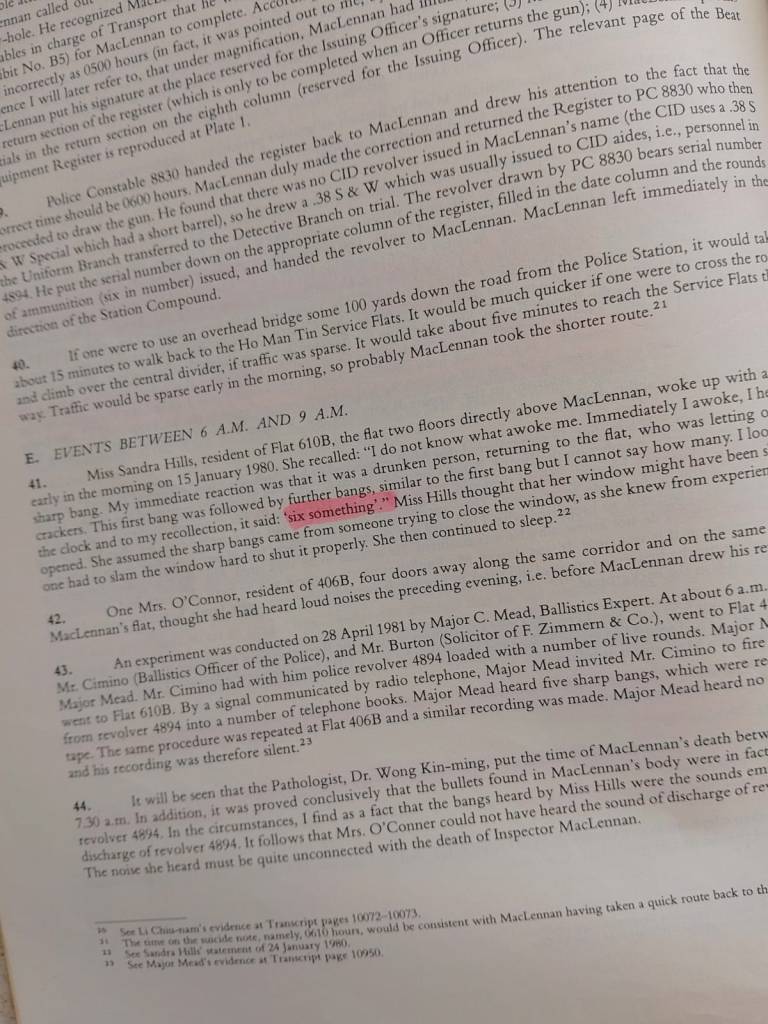

John Maclennan had been found with five bullet wounds in his torso, and the immediate police judgment was suicide. The kill shot went through his heart and liver, which for right-handed John meant he had to angle the gun down and across his body, a contortion that would enable him to hit his heart at the top left, the bullet travelling across to the lower right, piercing his liver. As a suicide it didn’t make sense at all.

John Mac. had been investigating ‘the gay question’ in Hong Kong and the story of Chinese rent boys. At that point in time it was a still a capital crime on the Hong Kong statutes, meaning a man could be sentenced to death for being homosexual. At that time, the Police Commissioner, Roy Henry, lived alone except for his Malay servant boy. At that time many of the Hong Kong establishment were known gays.

I was the producer of the hour. I worked with two journalists on the report, one a young Englishman (twenties like me) and a Canadian Chinese girl.

We did a good job, beginning the hour with an early morning image of MacLennan’s block where he had an apartment, in which he was found dead. Over the still early morning image of his building came the startling sound of five gunshots in more or less the manner audio witnesses said they heard them.

We had good interviewees with one of the best quotes on Justice Yang’s very detailed report, from a gay Englishman: ‘I just want to put the whole inquiry behind me.’

To put it bluntly, the whole issue by late twentieth century standards was a joke and the conservative justice, Yang, didn’t spare any establishment members with his critique. Nor did we. Though we followed the report to the letter.

Still, the backlash was swift. The establishment got its revenge. Our phones were tapped by Special Branch. The English reporter left his job. As a founding program member, I was taken off Here and Now, demoted to overseeing English translations from the Chinese service. The Canadian Chinese woman, one of the few Chinese on H&N was left alone.

Where was Stuart W. and his desire for more journalism. Nowhere. He stayed on to become Director of Broadcasting, getting for himself a red Mercedes convertible. Our program was gutted, a sycophant given the role of editor.

Yet some demotions are good. Nobody wants to work for a sycophant, a yes man, who is also boring as an individual. Maybe those lack of qualities are all joined at the hip generally in humanity. When the sycophant was made the new editor of the program of which several of us were founding members Here and Now was finished. It had developed a profile and a good following, yet it seemed that Stuart W.’s interest in it in any real supportive sense was done and dusted as well.

It seemed to me that Stuart W. had moved on from the program anyway, personal ambition led him to eye the position of Director of Broadcasting which had become vacant. Personal desire also would soon lead him to a younger wealthy Chinese girlfriend who, being from a rich family, would present him with a Red Mercedes convertible with the licence plate DB1.

Who needs journalism when it is so easily corrupted. I was never a journalist. I was a filmmaker, but when we had journalism to do, I did my best and my best chance at journalism came with the hour-long program I and two other colleagues did on the inquiry into the death of police inspector John Maclennan. But if you tell the truth about powerful people you put yourself at risk.

I suppose Stuart W.’s relationship with other government departments, such as the Police force and Attorney General’s department, was at risk when we did our work properly on the strange death of the police inspector. Pressure from the Chief of Police, Roy Henry, and the equally inquiry criticised Attorney General, would have put Stuart W. in a bad career position. It seems to me he succumbed to that pressure.

Looking back my demotion was a blessing in disguise. I was given oversight of converting a Chinese program to English which took me maximum two to three days to do. I had time to do other things. Why did I stay on? My two and half year contract which I signed was approaching two years. It had a gratuity bonus payout at its end which I definitely didn’t want to throw away. I found other things to do, photography, I trained as a scuba diver went on a trip to Nouvelle Calendonie dived at a remote reef with sharks and and began running to get super fit – I ran two marathons Hong Kong and London 1983 – I found running marathons was actually a fun thing to do.

What did I learn during six years making films in Hong Kong? You have to make decisions on the run. You have to endure the people around you who can fail you. The turn-around of a week to week production schedule is demanding. You had to plan but then be ready to throw the plan away, trust your judgment, not worry if some things didn’t work out. There is always more than one way.

I had so many interesting film projects. To mention a few others: China twice for NIRT. The Trojan Horse for RTHK following Hong Kong fashion designers to Paris’s Prêt à porter, a cinéma vérité film. Another on how Hong Kong people and troops held captive during the Japanese occupation created entertainment. A film on an island two miles off the coast of China where Chinese refugees boated or swam to. A film on eye operations for diabetics. There were so many. My last film on the new HK Jubilee Sports Centre made just before leaving my job didn’t please the Centre’s CEO who expected a puff piece. Still it worked.